English as a Global Language

What is a Global Language?

There is no official definition of “global” or “world” language, but it essentially refers to a language that is learned and spoken internationally, and is characterized not only by the number of its native and second language speakers, but also by its geographical distribution, and its use in international organizations and in diplomatic relations. A global language acts as a “lingua franca”, a common language that enables people from diverse backgrounds and ethnicities to communicate on a more or less equitable basis.

Historically, the essential factor for the establishment of a global language is that it is spoken by those who wield power. Latin was the lingua franca of its time, although it was only ever a minority language within the Roman Empire as a whole. Crucially, though, it was the language of the powerful leaders and administrators and of the Roman military – and, later, of the ecclesiastical power of the Roman Catholic Church – and this is what drove its rise to (arguably) global language status. Thus, language can be said to have no independent existence of its own, and a particular language only dominates when its speakers dominate (and, by extension, fails when the people who speak it fail).

The influence of any language is a combination of three main things: the number of countries using it as their first language or mother-tongue, the number of countries adopting it as their official language, and the number of countries teaching it as their foreign language of choice in schools. The intrinsic structural qualities of a language, the size of its vocabulary, the quality of its literature throughout history, and its association with great cultures or religions, are all important factors in the popularity of any language. But, at base, history shows us that a language becomes a global language mainly due to the political power of its native speakers, and the economic power with which it is able to maintain and expand its position.

Why is a Global Language Needed?

It is often argued that the modern “global village” needs a “global language”, and that (particularly in a world of modern communications, globalized trade and easy international travel) a single lingua franca has never been more important. With the advent since 1945 of large international bodies such as the United Nations and its various offshoots – the UN now has over 50 different agencies and programs from the World Bank, World Health Organization and UNICEF to more obscure arms like the Universal Postal Union – as well as collective organizations such as the Commonwealth and the European Union, the pressure to establish a worldwide lingua franca has never been greater. As just one example of why a lingua franca is useful, consider that up to one-third of the administration costs of the European Community is taken up by translations into the various member languages.

Some have seen a planned or constructed language as a solution to this need. In the short period between 1880 and 1907, no less than 53 such “universal artificial languages” were developed. By 1889, the constructed language Volapük claimed nearly a million adherents, although it is all but unknown to day. Today the best known is Esperanto, a deliberately simplified language, with just 16 rules, no definite articles, no irregular endings and no illogical spellings. A sentence like “It is often argued that the modern world needs a common language with which to communicate” would be rendered in Esperanto as “Oni ofte argumentas ke la moderna mondo bezonas komuna linguon por komunikado”, not difficult to understand for anyone with even a smattering of Romance languages.

Many of these universal languages (including Esperanto) were specifically developed with the view in mind that a single world language would automatically lead to world peace and unity. Setting aside for now the fact that such languages have never gained much traction, it has to be said this assumption is not necessarily well-founded. For instance, historically, many wars have broken out within communities of the same language (e.g. the British and American Civil Wars, the Spanish Civil War, Vietnam, former Yugoslavia, etc) and, on the other hand, the citizens of some countries with multiple languages (e.g. Switzerland, Canada, Singapore, etc) manage to coexist, on the whole, quite peaceably.

Is a Global Language Necessarily “A Good Thing”?

While its advantages are self-evident, there are some legitimate concerns that a dominant global language could also have some built-in drawbacks. Among these may be the following:

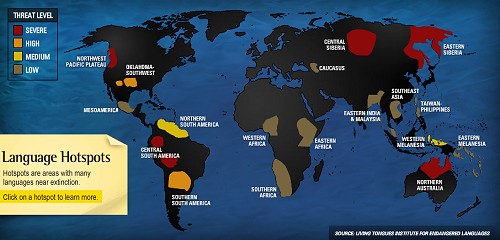

- There is a risk that the increased adoption of a global language may lead to the weakening and eventually the disappearance of some minority languages (and, ultimately, it is feared, ALL other languages). It is estimated that up to 80% of the world’s 6,000 or so living languages may die out within the next century, and some commentators believe that a too-dominant global language may be a major contributing factor in this trend. However, it seem likely that this is really only a direct threat in areas where the global language is the natural first language (e.g. North America, Australia, Celtic parts of Britain, etc). Conversely, there is also some evidence that the very threat of subjugation by a dominant language can actually galvanize and strengthen movements to support and protect minority languages (e.g. Welsh in Wales, French in Canada).

- There is concern that natural speakers of the global language may be at an unfair advantage over those who are operating in their second, or even third, language.

- The insistence on one language to the exclusion of others may also be seen as a threat to freedom of speech and to the ideals of multiculturalism.

- Another potential pitfall is linguistic complacency on the part of natural speakers of a global language, a laziness and arrogance resulting from the lack of motivation to learn other languages. Arguably, this can already be observed in many Britons and Americans.

Is English a Global Language?

As can be seen in more detail in the section on English Today, on almost any basis, English is the nearest thing there has ever been to a global language. Its worldwide reach is much greater than anything achieved historically by Latin or French, and there has never been a language as widely spoken as English. Many would reasonably claim that, in the fields of business, academics, science, computing, education, transportation, politics and entertainment, English is already established as the de facto lingua franca.

The UN, the nearest thing we have, or have ever had, to a global community, currently uses five official languages: English, French, Spanish, Russian and Chinese, and an estimated 85% of international organizations have English as at least one of their official languages (French comes next with less than 50%). Even more starkly, though, about one third of international organizations (including OPEC, EFTA and ASEAN) use English only, and this figure rises to almost 90% among Asian international organizations.

As we have seen, a global language arises mainly due to the political and economic power of its native speakers. It was British imperial and industrial power that sent English around the globe between the 17th and 20th Century. The legacy of British imperialism has left many counties with the language thoroughly institutionalized in their courts, parliament, civil service, schools and higher education establishments. In other counties, English provides a neutral means of communication between different ethnic groups.

But it has been largely American economic and cultural supremacy – in music, film and television; business and finance; computing, information technology and the Internet; even drugs and pornography – that has consolidated the position of the English language and continues to maintain it today. American dominance and influence worldwide makes English crucially important for developing international markets, especially in the areas of tourism and advertising, and mastery of English also provides access to scientific, technological and academic resources which would otherwise be denied developing countries.

Is English Appropriate for a Global Language?

Some have also argued that there are other intrinsic features of the English language that set it apart, and make it an appropriate choice as a global language, and it may be worthwhile investigating some of these claims:

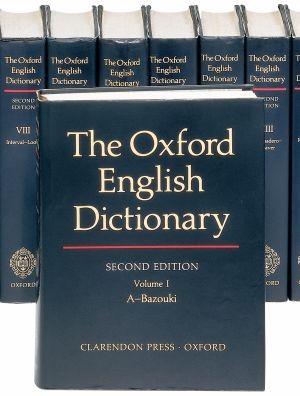

- The richness and depth of English’s vocabulary sets it apart from other languages. The 1989 revised “Oxford English Dictionary” lists 615,000 words in 20 volumes, officially the world’s largest dictionary. If technical and scientific words were to be included, the total would rise to well over a million. By some estimates, the English lexicon is currently increasing by over 8,500 words a year, although other estimates put this as high as 15,000 to 20,000. It is estimated that about 200,000 English words are in common use, as compared to 184,000 in German, and mere 100,000 in French. The availability of large numbers of synonyms allows shades of distinction that are just not available to non-English speakers and, although other languages have books of synonyms, none has anything on quite the scale of “Roget’s Thesaurus”. Add to this the wealth of English idioms and phrases, and the available material with which to express meaning is truly prodigious, whether the intention is poetry, business or just everyday conversation.

- It is a very flexible language. One example of this is in respect of word order and the ability to phrase sentences as active or passive (e.g. I kicked the ball, or the ball was kicked by me). Another is in the ability to use the same word as both a noun and a verb (such as drink, fight, silence, etc). New words can easily be created by the addition of prefixes or suffixes (e.g. brightness, fixation, unintelligible, etc), or by compounding or fusing existing words together (e.g. airport, seashore, footwear, etc). Just how far English’s much-vaunted flexibility should go (or should be allowed to go) is a hotly-debated topic, though. For example, should common but incorrect usages (e.g. disinterested to mean uninterested; infer to mean imply; forego to mean forgo; flout to mean flaunt; fortuitous to mean fortunate; etc) be accepted as part of the natural evolution of the language, or reviled as inexcusable sloppiness which should be summarily nipped in the bud?

- Its grammar is generally simpler than most languages. It dispenses completely with noun genders (hence, no dithering between le plume or la plume, or between el mano or la mano), and often dispenses with the article completely (e.g. It is time to go to bed). The distinction between familiar and formal addresses were abandoned centuries ago (the single English word you has seven distinct choices in German: du, dich, dir, Sie, Ihnen, Ihr and euch). Case forms for nouns are almost non-existent (with the exception of some personal pronouns like I/me/mine, he/him/his, etc), as compared to Finnish, for example, which has fifteen forms for every noun, or Russian which has 12. In German, each verb has 16 different forms (Latin has a possible 120!), while English only retains 5 at most (e.g. ride, rides, rode, riding, ridden) and often only requires 3 (e.g. hit, hits, hitting).

- Some would also claim that it is also a relatively simple language in terms of spelling and pronunciation, although this claim is perhaps more contentious. While it does not require mastery of the subtle tonal variations of Cantonese, nor the bewildering consonant clusters of Welsh or Gaelic, it does have more than its fair share of apparently random spellings, silent letters and phonetic inconsistencies (consider, for example, the pronunciation of the “ou” in thou, though, thought, through, thorough, tough, plough and hiccough, or the “ea” in head, heard, bean, beau and beauty). There are somewhere between 44 and 52 unique sounds used in English pronunciation (depending on the authority consulted), almost equally divided between vowel sounds and consonants, as compared to 26 in Italian, for example, or just 13 in Hawaiian. This includes some sounds which are notoriously difficult for foreigners to pronounce (such as “th”, which also comes in two varieties, as in thought and though, or in mouth as a noun and mouth as a verb), and some sounds which have a huge variety of possible spellings (such as the sound “sh”, which can be written as in shoe, sugar, passion, ambitious, ocean, champagne, etc, or the long “o” which can be spelled as in go, show, beau, sew, doe, though, depot, etc). In its defence, though, its consonants at least are fairly regular in pronunciation, and it is blessedly free of the accents and diacritical marks which festoon many other languages. Also, its borrowings of foreign words tend to preserve the original spelling (rather than attempting to spell them phonetically). It has been estimated that 84% of English spellings conform to general patterns or rules, while only 3% are completely unpredictable (3% of a very large vocabulary is, however, still quite a large number, and this includes such extraordinary examples as colonel, ache, eight, etc). Arguably, some of the inconsistencies do help to distinguish between homophones like fissure and fisher; seas and seize; air and heir; aloud and allowed; weather and whether; chants and chance; flu, flue and flew; reign, rein and rain; etc.

- Some argue that the cosmopolitan character of English (from its adoption of thousands of words from other languages with which it came into contact) gives it a feeling of familiarity and welcoming compared to many other languages (such as French, for example, which has tried its best to keep out other languages).

- Despite a tendency towards jargon, English is generally reasonably concise compared to many languages, as can be seen in the length of translations (a notable exception is Hebrew translations, which are usually shorter than their English equivalents by up to a third). It is also less prone to misunderstandings due to cultural subtleties than, say, Japanese, which is almost impossible to simultaneously translate for that reason.

- The absence of coding for social differences (common in many other languages which distinguish between formal and informal verb forms and sometimes other more complex social distinctions) may make English seem more democratic and remove some of the potential stress associated with language-generated social blunders.

- The extent and quality of English literature throughout history marks it as a language of culture and class. As a result, it carries with it a certain legitimacy, substance and gravitas that few other languages can match.

On balance, though, the intrinsic appeal of English as a world language is probably overblown and specious, and largely based on chauvinism or naïveté. It is unlikely that linguistic factors are of great importance in a language’s rise to the status of world language, and English’s position today is almost entirely due to the aforementioned political and economic factors.

What About The Future?

Although English currently appears to be in an unassailable position in the modern world, its future as a global language is not necessarily assured. In the Middle Ages, Latin seemed forever set as the language of education and culture, as did French in the 18th Century. But circumstances change, and there are several factors which might precipitate such a change once again.

There are two competing drives to take into account: the pressure for international intelligibility, and the pressure to preserve national identity. It is possible that a natural balance may be achieved between the two, but it should also be recognized that the historical loyalties of British ex-colonies have been largely replaced by pragmatic utilitarian reasoning.

The very dominance of an outside language or culture can lead to a backlash or reaction against it. People do not take kindly to having a language imposed on them, whatever advantage and value that language may bring to them. As long ago as 1908, Mahatma Gandhi said, in the context of colonial India: “To give millions a knowledge of English is to enslave them”. Although most former British colonies retained English as an official language after independence, some (e.g. Tanzania, Kenya, Malaysia) later deliberately rejected the old colonial language as a legacy of oppression and subjugation, disestablishing English as even a joint official language. Even today, there is a certain amount of resentment in some countries towards the cultural dominance of English, and particularly of the USA.

As has been discussed, there is a close link between language and power. The USA, with its huge dominance in economic, technical and cultural terms, is the driving force behind English in the world today. However, if the USA were to lose its position of economic and technical dominance, then the “language loyalties” of other countries may well shift to the new dominant power. Currently, perhaps the only possible candidate for such a replacement would be China, but it is not that difficult to imagine circumstances in which it could happen.

A change in population (and population growth) trends may prove to be an influential factor. The increasing Hispanic population of the USA has, in the opinion of some commentators, already begun a dilution of the “Englishness” of the country, which may in turn have repercussions for the status of the English language abroad. Hispanic and Latino Americans have accounted for almost half of America’s population growth in recent years, and their share of the population is expected to increase from about 16% today to around 30% by 2050. Some even see the future possibility of a credible secessionist movement, similar to that for an independent Quebec in Canada, and there has been movements within the US Republican party (variously called “English First” or “Official English” or “US English”) to make English the nation’s official language in an attempt to reduce the significance of Spanish. Official policies of bilingualism or multilingualism in countries with large minority language groups, such as are in place in countries like Canada, Belgium and Switzerland, are an expensive option and fraught with political difficulties, which the USA would prefer to avoid.

A 2006 report by the British Council suggests that the number of people learning English is likely to continue to increase over the next 10-15 years, peaking at around 2 billion, after which a decline is predicted. Various attempts have been made to develop a simpler “controlled” English language suitable for international usage (e.g. Basic English, Plain English, Globish, International English, Special English, Essential World English, etc). Increasingly, the long-term future of English as a global language probably lies in the hands of Asia, and especially the huge populations of India and China.

Having said that, though, there may now be a critical mass of English speakers throughout the world which may make its continued growth impossible to stop or even slow. There are no comparable historical precedents on which to base predictions, but it well may be that the emergence of English as a global language is a unique, even an irreversible, event.