Language & Geography

National Boundaries

Language is no respecter of boundaries or national borders, and overlaps across borders are common. For example, German covers not only the traditional areas of Germany, Austria and most of Switzerland, but also spills over into Belgium, Denmark, Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, Poland, and several countries of the old Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union was a single country, it hosted about 150 separate languages, and almost half of the population spoke a language other than Russian as its native tongue (a quarter did not speak Russian at all!)

Conversely, the languages of some different countries may be much closer than those spoken within the same country. Romanian and Moldavian are essentially the same languages just with different names, and Serbian and Croatian are fundamentally the same except that Serbian uses the Cyrillic alphabet and Croatia uses Western characters. Although Celtic Gaelic speakers of Scotland generally cannot understand the Celtic spoke in nearby Wales, they are usually able to understand the Celtic spoken much further afield in the Brittany region of France.

The so-called Romance languages (such as French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and Romanian) all developed out of Latin, and there remain many parallels between the languages, to the extent that Spaniards can usually understand written Italian and Portuguese (and vice versa) sufficiently well to carry on a correspondence, although spoken conversation tends to be more difficult. The modern language that most closely resembles ancient Latin is Lugurodese, an Italian dialect spoken in central Sardinia, although it should be remembered that classical Latin was exclusively a literary and scholarly language, and spoken or “vulgar” Latin (out of which the Romance languages largely developed) was substantially different. Romania, isolated in Eastern Europe and surrounded only by Slavic languages, is closer to Latin than even Italian, and is the only Romance language to keep the declensions and the neuter gender from classical Latin.

Most of the languages of Europe developed out of the Indo-European family of languages, however there are some exceptions. The Basque language, spoken in a small area of northeastern Spain and southwestern France, is a completely unrelated language isolate, as is the Georgian language of the Caucasus region of eastern Europe. Maltese is a Semitic language, closer to Arabic but written using the Latin alphabet. Estonian, Finnish and Hungarian are all Finno-Ugric languages, a subfamily of the Uralic language family. Turkish is a Turkic language, more closely related to the Altaic languages of Mongolian, Korean and Japanese than to Indo-European languages.

Multilingual Countries

In many countries, perhaps even the majority of countries, there are at least two native languages. In Belgium, for example, many towns have both French and Dutch names which are used by the French- and Flemish-speaking population (e.g. Bruges and Brugge, Liège and Luik, Tournai and Doornik, etc). In Luxembourg, the inhabitants use French at school, German for reading newspapers and Luxemburgish (a local German dialect) at home.

Multilingual speakers outnumber monolingual speakers in the world’s population. By some estimates, 50% of the population of Africa is multilingual. Some countries have not just two or three languages but hundreds, and India boasts 1,600 languages and dialects. South Africa has no less than eleven official languages: Afrikaans, English, Southern Ndebele, Northern Sotho, Southern Sotho, Swazi, Tsonga, Tswana, Venda, Xhosa and Zulu. In West Africa, an English-based pidgin language, developed during the Atlantic slave trade years, still serves as a common lingua franca between several different countries with distinct and mutually unintelligible languages.

But not all speakers in a multilingual society need to be multilingual. Some countries may have multilingual policies and recognise several official languages (such as English and French in Canada), but particular languages may be associated only with particular regions in the state (e.g. Québec, New Brunswick). In Scandinavia, many, if not most, speakers of Swedish and Norwegian (and also of Norwegian and Danish) can communicate with each other by speaking their respective languages, and just avoiding words that are not found in the other language, or that may be misunderstood. A similar phenomenon occurs in Argentina, where the similar but distinct languages of Spanish and Italian are both widely spoken.

Multiple languages within a country can also lead to political problems, as witnessed by the simmering resentment of the Dutch-speaking majority in Belgium, the sometimes radical tactics of the French-speaking Québecois in Canada and Welsh language campaigners in English-dominated Wales, and the full-blooded terrorism of the Basque organization ETA in the name of linguistic and cultural independence.

However, despite such activism, and apparently regardless of government support or otherwise, minority languages in multilingual countries are generally on the decline. There have been isolated victories, such as the increasing usage of Hawaiian and Scottish Gaelic, but there have been many more set-backs. For instance, Irish Gaelic appears moribund, and even Welsh is still declining slowly despite the investment of millions in government money. The last native speaker of Manx, a Celtic language spoken on the tiny Isle of Man, died in the 1960s. Further afield, Ubykh, a highly complex Caucasian language with 82 consonants and just 3 vowels, once spoken by 50,000 people in the Crimea region of eastern Europe, went the same way in 1992.

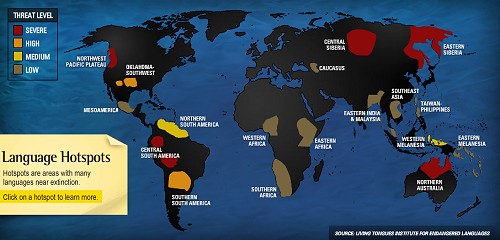

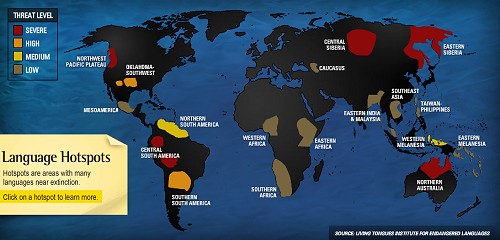

Endangered Languages

It is difficult to pinpoint the total number of contemporary languages in the world, but around 6,000 is a good broad estimate. The Ethnologue database identifies over 6,900 active languages, of which 33% are in Asia and 30% in Africa. Of these, UNESCO categorizes about 2,500 to be in one of five levels of endangerment: unsafe, definitely endangered, severely endangered, critically endangered and extinct. In recent times alone, more than 2000 languages have already become extinct around the world. It is estimated by some that up to 80% of the world’s living languages may die out within the next century.

The issue is far from clear, though. Some languages in Indonesia, for example, may have tens of thousands of current speakers, but may nevertheless be endangered because children are no longer learning them, as speakers shift to using the national Indonesian language (or a local Malay variety) in place of local languages. Others, like the Andamanese languages of the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal, may have only a hundred speakers each, but may be considered very much alive if they are the primary language of a community and the first (or only) language of all children in that community.

It is possible to revitalize dead or moribund languages. Hebrew is perhaps the only example of a language which has gone from being extinct as a spoken language to being a national language with millions of first language speakers. But Cornish has also been successfully revived, after well over a century of extinction, and now has a growing number of speakers (currently in the thousands). Attempts to revitalise Irish Gaelic, Welsh in Wales, Galician in Galicia, Basque in Basque Country, Catalan in Catalonia and some Amerindian languages have, however, met with mixed success.